11 Female Abstract Expressionists You Should Know, from Joan Mitchell to Alma Thomas

Abstract Expressionism is largely remembered as a movement defined by the paint-slinging, hard-drinking machismo of its poster boys Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. But the women who helped develop and push the style forward have largely fallen out of the art-historical spotlight, marginalized during their careers (and now in history books) as students, disciples, or wives of the their more-famous male counterparts rather than pioneers in their own right. (An exception is Helen Frankenthaler, whose transcendent oeuvre is often the only female practice referred to in scholarship and exhibitions around action painting.)

Even when these artists were invited into the members- and male-only Eighth Street Club to discuss abstraction and its ability to channel emotional states—as was the case with Perle Fine, Joan Mitchell, and Mary Abbott—their work rarely sold as well or was written about as widely or favorably. And these women received far fewer solo exhibitions than their male contemporaries. Some even changed their names, like Michael West, in an effort to combat the era’s sexism, or incorporated into their work tacit challenges to the status quo, as Elaine de Kooning did in her “Faceless Men” series.

Now in a long-overdue exhibition at the Denver Art Museum, a sizable, boundary-pushing group of female Abstract Expressionists are finally getting their due. Below, we spotlight some of the most innovative practitioners (admittedly, there are many more than 11).

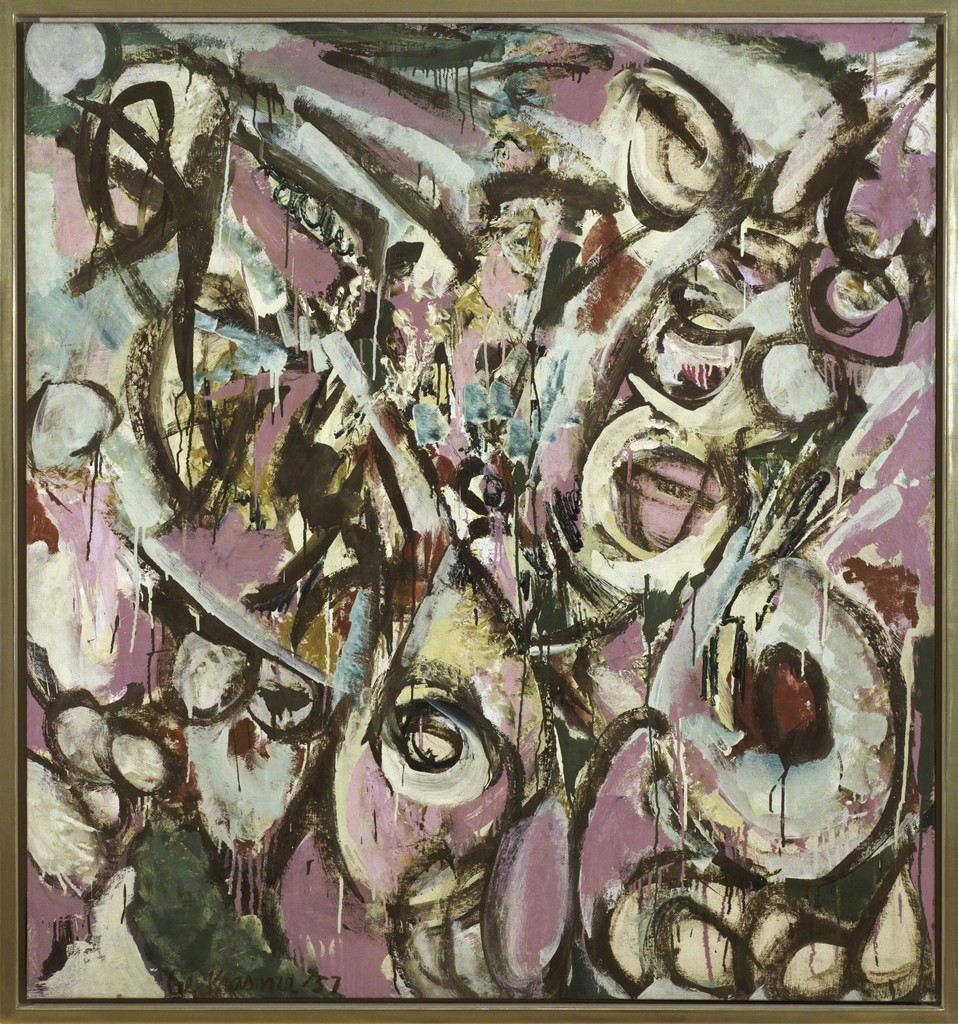

In 1937, after several years studying with artist Hans Hofmann at his eponymous school, Krasner painted a work that Hofmann described as “so good you would not know that it was done by a woman.” Throughout her career, Krasner, one of the earliest and most innovative AbEx practitioners, would struggle against the marginalization of women artists, even changing her first name from Lena to the gender-ambiguous Lee in the 1940s.

While she introduced her husband, Jackson Pollock, to the ideas and key progenitors of the movement for which he would become the posterboy, her relation to Pollock often superceded her own reputation as an artist. Krasner is one of the few artists on this list who saw a retrospective of her work mounted during her lifetime (in 1983, a year before her death). But her paintings, which burst with fierce, swooping lines and swollen shapes reminiscent of body parts, have only recently begun to receive their due as integral to shaping Abstract Expressionism and its legacy. Her 1957 magnum opus, The Seasons, which stretches 17 feet wide, is now the centerpiece of the Whitney Museum’s seventh-floor hanging.

De Kooning was a fixture of New York’s tight-knit Abstract Expressionist cohort, which included her husband Willem de Kooning, though she set herself apart by making portraits. Her compositions were edged with the movement’s high-octane gestures, as well as her own frustration with the marginalization of female artists. Her “Faceless Men” series, for instance, obscured the features of her more famous male contemporaries, like post-war poet and art critic Frank O’Hara. They were unveiled at her first solo exhibition at the Stable Gallery in 1952.

A sense of quivering energy pervades all facets of de Kooning’s diverse body of work, which also includes ebullient abstractions inspired by landscapes, bullfights, and the Lascaux cave paintings. “I wanted a sense of surfaces being in motion,” she explained of her canvases. A frequent contributor to ARTNews, she was also a passionate and eloquent exponent of the AbEx cause, expressing the movement’s animus succinctly, with phrases like: “A painting to me is primarily a verb, not a noun, an event first and only secondarily an image.”

In the early 1940s, when Fine was in her mid-30s, she rented a small, cold water flat that doubled as her studio on Manhattan’s 8th Street, the main drag of Abstract Expressionist activity and discussion. Across the street, the Hans Hofmann School buzzed with students eager to set objectivity aside and take up pure abstraction—Fine was one of them. Around the corner, Hofmann, de Kooning, and other AbEx pioneers discussed painting and swilled booze at The Club, their members-only haunt. Fine was one of the first and very few women allowed through its doors.

After moving to East Hampton with her husband, the photographer and art director Maurice Berezov, Fine made some of her most ambitious paintings—compositions that surged with deep passages of black paint and textured areas of collage. She worked on the floor to create these, moving across them using an elevated plank. Despite her innovative exploration of Abstract Expressionism, which she fused with an interest in the pure forms of Neo-Plasticism, Fine was not included in the Whitney’s 1978 show “Abstract Expressionism: The Formative Years,” which she contested in two letters to the museum. She later became a renowned professor at Hofstra University, but stated: “I never thought of myself as a student or teacher, but as a painter. When I paint something I am very much aware of the future. If I feel something will not stand up 40 years from now, I am not interested.”

Like Krasner, West was an early adopter of Abstract Expressionism and one of the movement’s boldest artists. As early as 1932, she studied with Hofmann alongside the painter-gallerist Betty Parsons and artist Louise Nevelson, but soon moved to other instructors because, as stated in her plucky style, she’d had “enough of maestros.” At the time, she made paintings that mingled elements of Cubism and Neo-Plasticism, but soon moved towards abstraction, a shift no doubt influenced by her intimate relationship with painter Arshile Gorky (she refused his marriage proposals several times, choosing independence).

In the late 1930s, they together concocted a new, masculine first name for West, who was born Corinne Michelle. She returned to New York after a stint in Rochester, and a 1945 exhibition included her work alongside the likes of Milton Avery and Mark Rothko. After the war, she responded to the fear and frustration of the atomic age with angry lashings of pigment; she often covered earlier paintings with new tangles of seething brushwork. They became thick, turbid all-over abstractions, painted directly from the tube or with a palette knife, embedded with sand and detritus, and imbued with existential titles like “Nihilism” and “Atonement.” Despite her innovations and efforts to fight the marginalization she felt as a woman (changing her name, dressing in menswear), she is largely left out of history books and exhibitions on avant-garde art of the 1940s and Abstract Expressionism.

While Thomas, who is featured in a solo exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem this summer, is best known for her geometric compositions of blazing color, her early paintings from the 1950s are rooted in the AbEx style, which unlocked her nimble experiments with hue and form. In 1924, she was the first graduate of Howard University’s fledgling Fine Art program, but she devoted the majority of her adult life to teaching high school, until she focused on her practice once again in 1950. Her all-over canvases evince a deep curiosity with color and its ability to convey emotion. Often inspired by landscapes, science, and the cosmos, they pulse with their deftly modulated palettes. Light blues bleed into darks with a sense of rushing, fluid movement.

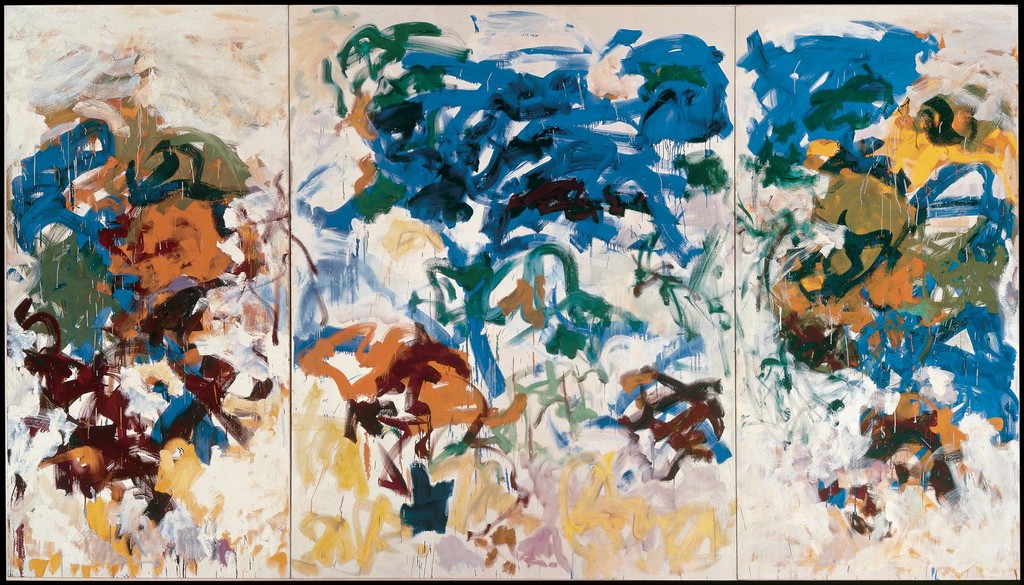

When Mitchell settled in New York in 1950, after receiving her BFA at the Art Institute of Chicago, she immediately became a mainstay on the avant-garde scene, thanks to her fiery wit and exuberant abstractions that married writhing, lyrical lines with searing colors rendered like staccato notes. She was influenced not only by her contemporary painters, but also by writers and musicians—poet Frank O’Hara was a close friend, she was infatuated with jazz, and she frequented a bar where Miles Davis and Tennessee Williams were regulars.

In 1951, Mitchell was one of a handful of women included in the history-making “Ninth Street Show,” which cemented Abstract Expressionism as a movement to watch—as well as her own place amongst older practitioners like the de Koonings, Robert Motherwell, Hans Hofmann, Krasner, Pollock, and more. She became known as one of several “Second Generation” female Abstract Expressionists, along with Helen Frankenthaler and Grace Hartigan, and earned a coveted place at The Club, where she slung her ardent, often scathing opinions in salon conversations. “I’ve always painted out of omnipotence,” she once said.

In 1952, around the time her marriage ended in divorce (Mitchell is one of the few better-known women Abstract Expressionists who was not married to a famous male painter), she made good on her bold statements and mounted her first New York solo show. It would galvanize a steady stream of exhibitions in both the U.S. and Europe until her death.

In the early 1940s, around the time when she was modeling for Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, Abbott began taking classes at New York’s Art Student League. After separating from her husband in 1946, she settled on 10th Street among the Abstract Expressionists and took classes at Subjects of the Artist School, founded by Robert Motherwell in his 8th Street studio. Soon, she was making towering canvases characterized by sweeping brushstrokes that often merged into dense swarms of torrid, sensuous color inspired by annual winter trips to Haiti and the Virgin Islands.

Her broad brushstrokes were informed, in part, by her then-nascent dialogue with Willem de Kooning, who would be a lifelong sounding board and friend. She, like Mitchell, was also involved in the literary community and, in the late 1950s, began embedding text into her Action paintings as part of a collaboration with the New York School poet Barbara Guest. Painting at her home in the Hamptons to this day, she often describes her objective to “define the poetry of living space” through her work.

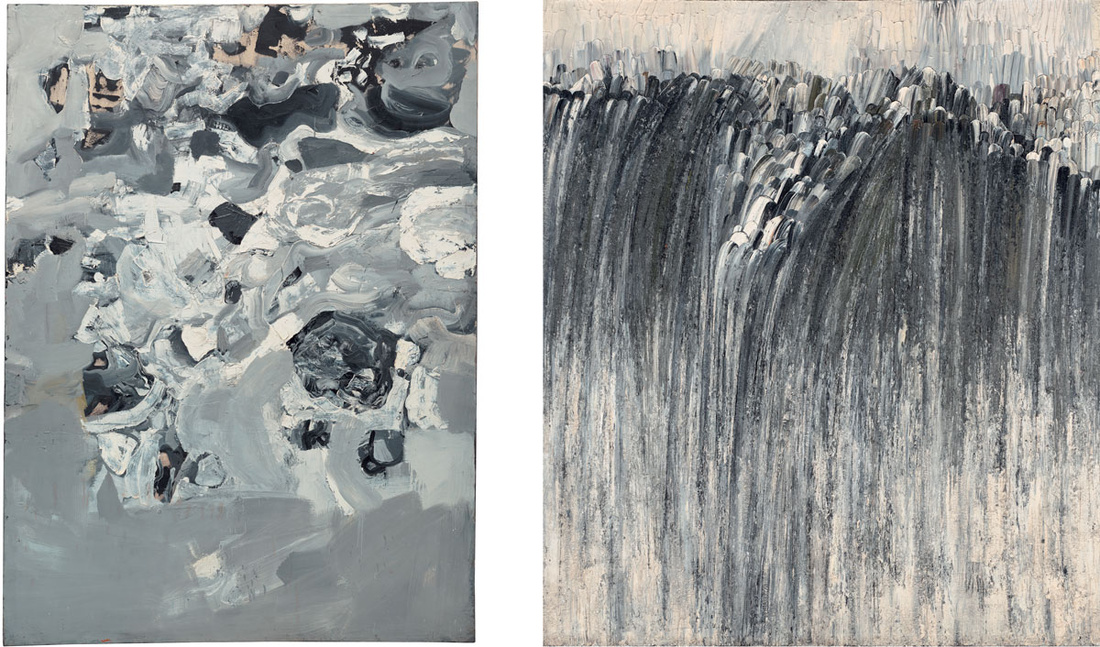

Left: Jay DeFeo, Untitled (Mountain series – Everest), 1955. © 2016 The Jay DeFeo Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Right: Jay DeFeo, Origin, 1956. © 2016 The Jay DeFeo Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Images courtesy of The Jay DeFeo Foundation.

Left: Jay DeFeo, Untitled (Mountain series – Everest), 1955. © 2016 The Jay DeFeo Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Right: Jay DeFeo, Origin, 1956. © 2016 The Jay DeFeo Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Images courtesy of The Jay DeFeo Foundation.

Born Mary Joan DeFeo, the enigmatic San Francisco painter assumed the nickname Jay and began making art in junior high school, mentored by an artist-neighbor named Michelangelo, while living in San Jose. She went on to study art at Berkeley, where she won a fellowship that prompted a trip to Europe and her first important series, a group of abstract paintings that fused her interests in Abstract Expressionism, Italian architecture, and prehistoric art. They also helped to introduce the use of a monochrome palette to all-over abstraction. By 1953, after a stop in New York, she was back in San Francisco and became a fast fixture on the scene, and a neighbor and friend to fellow artists Joan Brown, Sonia Gechtoff, David Getz, and others.

Over the decade, her work became thick with gesture, impasto, and mixed media, a shift that culminated in a terrifically imposing work that was as much her crucible as her magnum opus. DeFeo spent eight years, from 1958 to 1966, working solely on The Rose, a painting-cum-sculpture measuring over 10-feet tall, almost one-foot thick, and weighing over 2,000 pounds. An eviction noticed forced her to cease work on the piece, and also induced a several-year hiatus from artmaking. She only returned to the studio in the 1970s.

While the atmosphere in San Francisco was arguably less misogynistic than in New York, DeFeo no doubt still felt the gender inequalities of her time. In his review of DeFeo’s posthumous 2012-2013 retrospective—her first—at SFMOMA and the Whitney Museum, critic Peter Schjeldahl hypothesized the origins of her obsession with The Rose: “I surmise that she was hampered by, even while being nurtured on, a scene that was dominated by men… It’s conceivable that her withdrawal into obsessively reworking The Rose amounted to a tacit protest—a standup strike—against the pressures of her milieu.”

In 1951, Gechtoff moved from Philadelphia to San Francisco, where she installed her studio in “Painterland,” an affectionately titled building on Fillmore Street that was home to a bevy of abstract painters, including DeFeo, with whom she developed a friendship but also a rivalry. In this new environment, Gechtoff developed a unique approach: She coated a palette knife with several colors, then smeared them with swooping gestures onto her canvases. The lively paintings were celebrated, winning her a solo museum show at the de Young as early as 1957 and a spot in the Guggenheim’s seminal 1954 group exhibition “Younger American Painters” alongside de Kooning, Pollock, Franz Kline, and more—though it’s only recently that the historical influence of her work has been recognized and revived.

Another second-generation New York Abstract Expressionist, Hartigan (who occasionally showed under the pseudonym “George”) assumed but also challenged the non-objective style of her forebears, like de Kooning and Pollock, the latter whose work she saw for the first time at Betty Parsons Gallery in 1948. Though filled with shards of color and active gesture, her canvases never completely relinquished content. Often, they were embedded with social commentary that questioned the traditional role of women.

A 1954 series “Grand Street Brides” interrogated the construct of marriage by abstracting bridal shop mannequins (Hartigan married and divorced a handful of times). Other series, like her “Matador” paintings, explored sexual identity or incorporated elements from urban life and popular culture, although she passionately disapproved of the burgeoning Pop Artmovement. Unlike most women of the time, her work sold well, especially after her inclusion—as the only woman—in MoMA’s 1956 show “Twelve Americans,” which also featured paintings by Philip Guston and Franz Kline and resulted in the sale of her largest work to Nelson Rockefeller. But while she showed consistently in solo gallery shows and group museum exhibitions through the 1970s, interest dropped off in the mid-’70s, after which she taught and showed only sporadically until her death in 2008.

In 1950, Godwin, who was studying art in Virginia, met and befriended dancer and choreographer Martha Graham. The fateful run-in inspired Godwin to relocate to New York, where she began painting in abstract and with a dynamism influenced by Graham. In some paintings, you can almost feel the arc of her arm as it swooped across the canvas. “I can see her gestures in everything I do,” she once said of Graham.

Godwin fused this theatrical sense of movement with Hofmann’s color theories to produce rich tonal combinations. A long-term dialogue with Japanese painter Kenzo Okada also guided her practice and bolstered her interest in Zen Buddhism, as well as her intuitive approach to abstract painting. “When I recognize an emerging form, I respond intuitively by evolving complimentary sub-forms in colors and applications which feel supportive and foster development,” she said. “In studying color and its behavior, I have learned to trust my intuition.”

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario